Client Side App Variants

Feature branch builds (and more) for your statically generated SPA

The split between front-end and back-end has been a double-edged sword ever since the first developer chiseled JSX onto the wall of the tribal networking cave. What had the curiosity of this ancient heretic wrought? Along with the numerous advantages of client-rendered websites came numerous new challenges. Web developers started specializing to overcome these new challenges and explore this new way of building for the web. Today, common practice is to develop using separate teams of front-end developers and back-end developers as opposed to full stack developers.

For better and worse, this is the timeline we are in, and escape is futile.

One casualty of the front-end/back-end divide is the dedicated feature branch build, the place where your work-in-progress code can be deployed care-free as you build so that you and your teammates can see a fully integrated version of your changes. Today, with teams, repositories, and deployments split along technological lines, it can be difficult and time-consuming to find a way to make feature branch builds work. And what if you serve your static front-end assets via a simple, static file server?

At the possible expense of becoming another front-end heretic, I’ll tell you that you can trade one more round trip to the server for completely isolated front-end builds that are dynamically loaded without the need for special back-end logic.

Variants

Trying to achieve isolated feature branch builds solely through static, front-end code led me to something even more versatile. This slight architectural change allows you to deploy multiple builds of your application to a single authority (sub-domain + domain + port), with each build separated and loaded dynamically via a simple query parameter in the URL.

The system allows you to dynamically load:

- Feature branch builds: Our original goal. Deploy work-in-progress builds of your app as you develop a new feature.

- Snapshots of previous versions of your application: Perhaps you are working on rapidly changing data structures, and you’ll need to support the legacy versions of those structures for a time.

- Builds for different environments: Do some of your users need to connect to a different API?

- Builds for different personas: Maybe the marketing people at your company need to grab images of your new feature without any of the typical affordances rendered on screen.

- Builds for different tasks: Debugging in production can be easier when you are using the non-minified build and you’ve attached all your custom introspection UI tools.

All of these and more can coexist together on your file server, perfectly separated and preserved. Since this system is more than just “versions” or “feature branches,” we’ve settled on a new name: Variants.

The architectural shift

This entire article assumes you are working with a statically generated, SPA-like application. If you have more control over the server hosting your static front end assets, perhaps another solution is possible, though this one might still be better suited to your needs.

Additionally, if your deployment pipeline does not allow you to retain previous build artifacts in production, you won’t be able to use this approach.

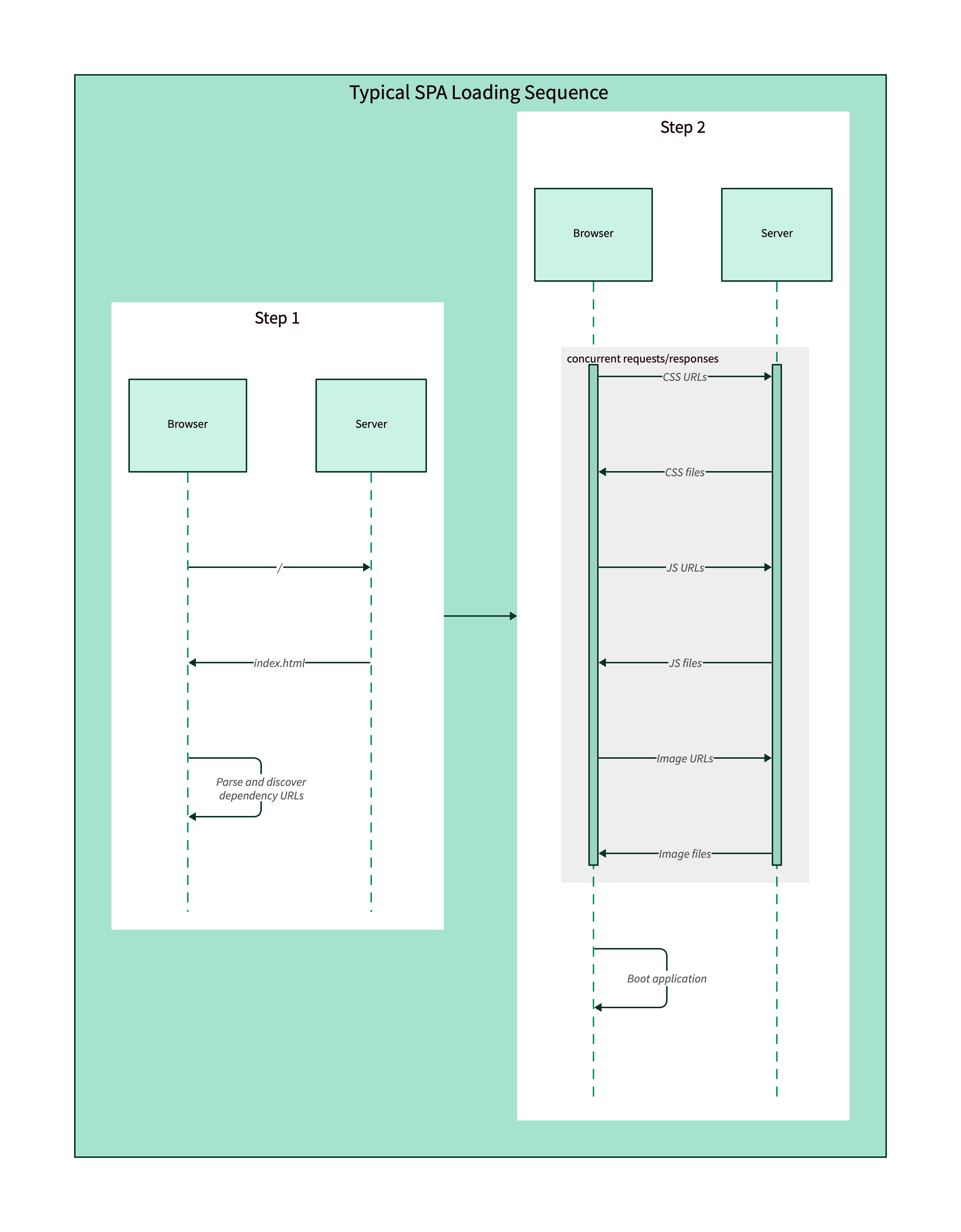

Typical static application loading

In a typical SPA-like website, your app is totally coupled to the index.html

file served at the root (and all other routes) of your site. It is responsible

for pulling in all the CSS and JS assets needed for the initial render of your

application. Your browser asks for the HTML file at some location on your site,

and the same exact file is always loaded, containing links to the same exact

assets every time. Once the site renders, perhaps your application recognizes

other assets that are required for your particular location and downloads those

as well, but by then your app is already running.

Every change to your application requires a brand-new build of index.html to

reference multiple new CSS and JS files.

|

|---|

| (Diagrams created at https://play.d2lang.com) |

Variant loading

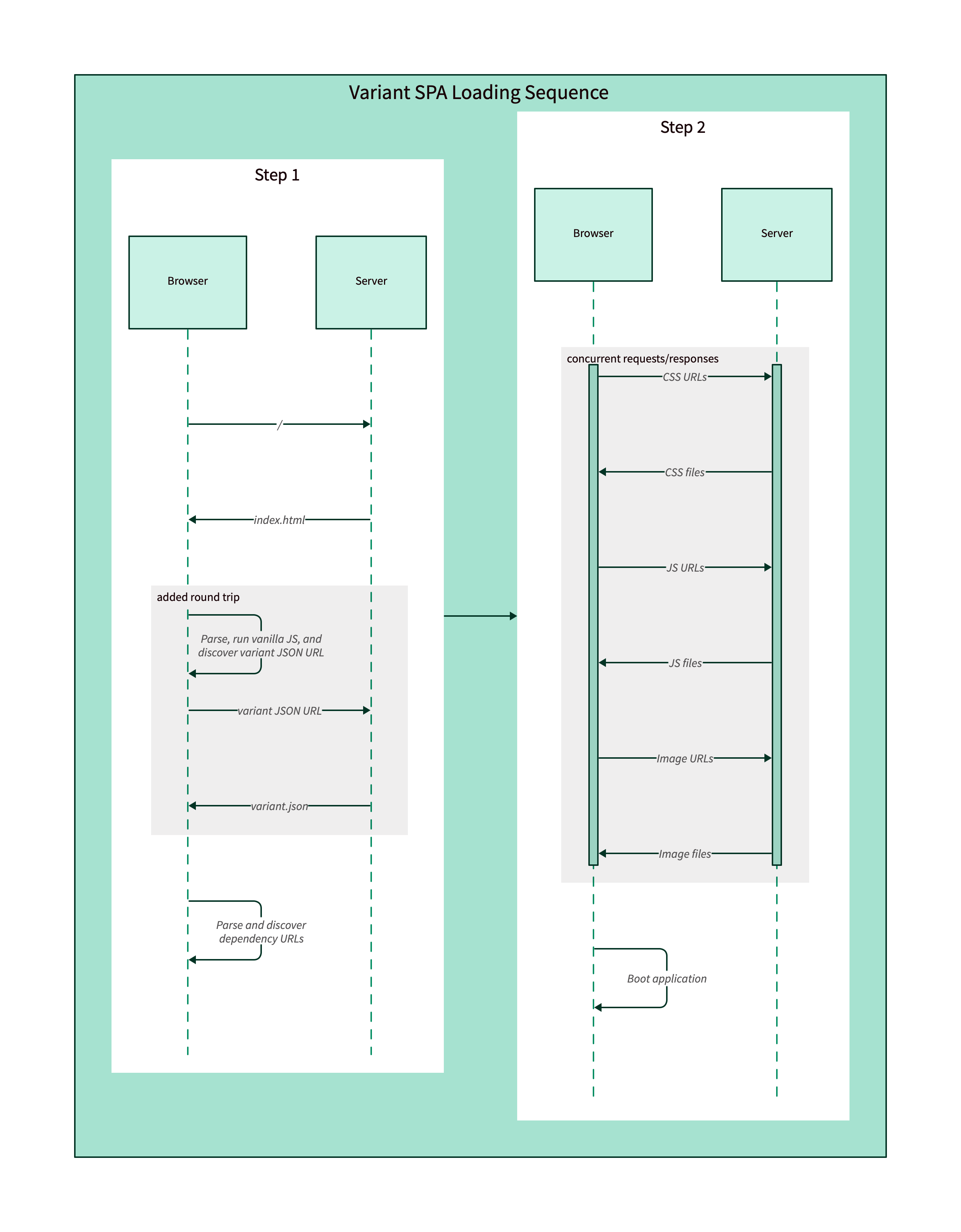

But what if the index.html file didn’t contain references to any of the assets

needed to run your application? What if it loaded your application assets

dynamically, based on the variant of the application you request?

# Loads the default variant

https://example.com

# Loads the `my_new_feature` variant

https://example.com?variant=my_new_featureInstead of baking our application’s static dependencies into the index.html

file, we can encapsulate the knowledge of those assets into a single JSON file

and give that file an arbitrary (variant) name. Since we are now pushing the

knowledge of our assets into a file that must be loaded separately from the

index file, we have the opportunity to run a tiny bit of JavaScript in the

browser before loading any application assets. That tiny bit of JavaScript can

either load the default variant JSON of our application, or it can load any

arbitrary variant JSON file we request by name via a query parameter. Once that

JSON file is loaded, we can use it to gather our actual application

dependencies.

|

|---|

| The only change from the “typical SPA loading sequence” is the added round trip in step 1. |

If your files are all properly fingerprinted —the name of the file contains a hash that forces it to be unique based on its exact contents —then you can keep all your old assets on your server and let your variant JSON files load whichever assets are required. Since every single build of your app can live side by side with each other, you can load whichever variant you want if you know the name of a JSON file that points to the proper dependencies.

Trade-offs

There are some downsides to this approach.

- Your users will be waiting for one more round trip to the file server before your app begins to boot.

- There is a fair amount of customization you’ll add to your Webpack config. (I won’t be showing how to achieve this same result with other build tools, though it can be done.)

- Typical turn-key static site hosts (Netlify, etc.) will prune your old build files each time you deploy, and that is completely antithetical to this approach.

- The different variants of your app may start battling each other for multiversal dominance.

Benefits

If you find yourself in a situation where you can accept the tradeoffs above,

there are plenty of situations in which loading any variant of your app via

the same exact index.html at the same location can be immensely useful. Using

variant deployment, you can

- Make a feature available to a select few people for testing;

- Revert to a previous build quickly if you discover a bug;

- Solve CORS problems exactly one time: not for production and feature branches;

- Load debugging tools directly into your bundle or load the non-production build against the production environment to track down a problem;

- Make snapshots of your application available in perpetuity for compatibility reasons;

- Serve a completely different application for each variant.

Our variant system at Trilliant Health

There are any number of ways you can build your application to use variants, but I’ll walk you through some of the concrete decisions we’ve made so you can get an idea of how you might want to do this yourself. Before we dig into some real code, let’s consider a few other ideas to layer on top of our current understanding of the variant system.

Problems with query parameters

You’ll note that I’ve described variant loading as being driven by a query

parameter called variant. But storing this kind of information in a query

parameter has some drawbacks.

- It kind of stinks that the whole application must be aware of this constantly-present query parameter. Any individual pages that need to manipulate the query parameters would need some defensive code to avoid dropping this parameter.

- And what if one of our internal users shares a URL from their browser that happens to contain a variant name that is not supposed to be used widely?

We should probably remove the query parameter from the page as soon as the app is loaded, since the only time we need the variant name is when we fetch our initial assets.

But then, what if the user refreshes their browser? Well, the variant name is

gone, and they’ll load the default variant of the app. Plus, the web

applications we build at Trilliant Health use Auth0 for authentication and so

must redirect to and from Auth0. On the way back, we’d have to include the

variant query parameter again, anyway.

We could solve these problems with Local Storage. Once the index page loads and

knows what variant to fetch, we can store the name of the variant in Local

Storage. On subsequent reloads, we can check for that Local Storage value and

use it if no variant exists in the query parameters. That solves our two

problems above and also keeps things working for Auth0, but it creates two more

problems:

- Users would not be able to load multiple variants of the app at once in multiple tabs unless they were very careful not to refresh the page.

- We’d have no good way to get our users back on the default variant when they are done with the variant they were using. They might get unwittingly stuck on a variant that isn’t getting updates.

Placing this kind of burden on our users is a no-go. Our apps should just work without the need for them know the intimate details of how our variant system behaves. So Local Storage is out. But Local Storage has a sibling called Session Storage with the same API that basically solves all the problems above. Session Storage behaves exactly like Local Storage except it is handled on a per-tab basis. When your tab is closed, all the Session Storage for that tab is cleared.

So, on page load, we store the variant in Session Storage, drop the query parameter, load the app, and let the entire application remain blissfully unaware of the entire variant system.

Variant-level config

In order to take full advantage of the variant system — with builds that are always current but have useful variations in behavior —we will probably want to store some configuration information inside the variants themselves. For example, the actual URL for your API server should probably be configured instead of discovered at runtime.

Since our Webpack config will already need to be generally aware of variants, we

also house some other values inside a variant config that we can replace using

the WebpackDefinePlugin. So in our applications, calls to our API server

resemble this:

fetch(`${API_BASE_URL}/some-endpoint`)And we let Webpack do the work of replacing API_BASE_URL with

"https://api.example.com" or "https://dev-api.example.com" or whatever other

URL makes sense for the given variant. We don’t need to maintain some kind of

runtime cross-reference for which variants talk to which server. It all goes

into the variant config itself and is resolved at build time.

“Give me the code”

Not everything you need will be included below, because this is some deeply custom code. But you should be able to merge these examples with your code and get things running.

We also are not going to tackle the actual deployment step in this article. At

Trilliant Health, we use Azure Blob Storage (ABS) to serve our apps. Our final

step in deployment is to upload all our files to ABS. Since our asset filenames

contain a unique hash, we just let it upload and overwrite files with

conflicting names. The result is that our new assets get uploaded with no

conflict, old assets are rewritten with the same content, and

{variantName}.json files get updated to point to new build assets.

index.html

This is a slightly simplified version of the index.html file we use for all

our SPAs at Trilliant Health.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Your title here</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="app"></div>

<script type="text/javascript">

// We use this IIFE to prevent global namespace pollution.

;(function () {

var defaultVariantName = "public"

/**

* @returns {string | null}

*/

function getStoredVariant() {

return window.sessionStorage.getItem("variant")

}

/**

* Changes the variant name in Session Storage. If we are

* changing to the default variant name, it removes the item

* from Session Storage entirely.

*

* @param {string} variantName

*/

function updateStoredVariant(variantName) {

variantName === defaultVariantName

? window.sessionStorage.removeItem("variant")

: window.sessionStorage.setItem("variant", variantName)

}

/**

* If the `variant` query param is available, this returns it.

*

* @returns {string | null}

*/

function getRequestedVariantViaSearchParam() {

return new URLSearchParams(document.location.search).get("variant")

}

/**

* Returns the URL for the JSON file that houses all the variant

* assets.

*

* @param {string} variantName

*/

function getUrlForVariant(variantName) {

// Date.now() ensures there is no browser caching. The named

// JSON file's contents can and will change often.

return "/variants/" + variantName + ".json?t=" + Date.now()

}

/**

* When the requested variant is missing, we render a message on

* screen to the user to let them know that the variant they

* requested does not exist and we render a link which will

* reset the variant to the default.

*

* @param {string} variantName

*/

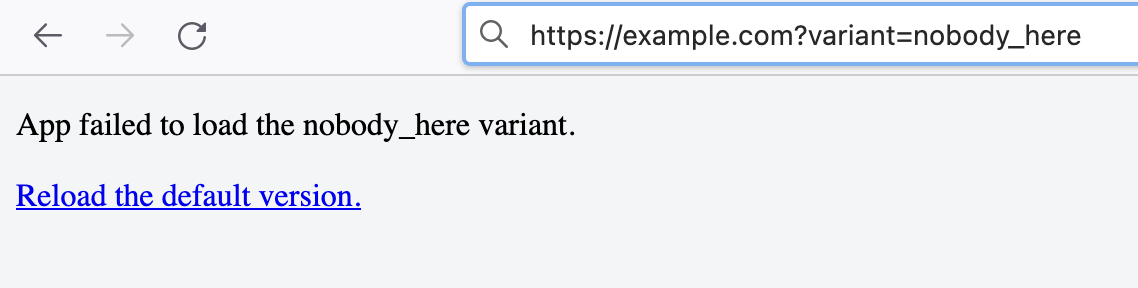

function updateViewExplainingMissingVariant(variantName) {

var root = document.querySelector("#root")

var p = document.createElement("p")

p.textContent = "App failed to load the " + variantName + " variant."

var link = document.createElement("a")

link.href =

// Drop all query params and just use the default variant.

// (You could do this differently and try to preserve all

// other query params aside from "variant" if you prefer.)

document.location.href.replace(/\?.*/, "") +

"?variant=" +

defaultVariantName

link.textContent = "Reload the default version."

root.append(p)

root.append(link)

}

/**

* Appends all the variant's `<script>` and `<link>` elements to

* the DOM

*

* @param {{ css: string[], scripts: string[] }} data

*/

function addAssetsToDom(data) {

data.scripts.forEach(function (src) {

var tag = document.createElement("script")

tag.src = src

tag.type = "text/javascript"

document.body.append(tag)

})

data.css.forEach(function (src) {

var tag = document.createElement("link")

tag.rel = "stylesheet"

tag.type = "text/css"

tag.href = src

document.head.append(tag)

})

}

// Definitions are done. Time for the action to begin. The

// variant query param overrides any stored variant. Then we

// check for a stored variant if that doesn't exist. Finally, we

// use the default if the other two functions return null.

var variantName =

getRequestedVariantViaSearchParam() ||

getStoredVariant() ||

defaultVariantName

updateStoredVariant(variantName)

window

.fetch(getUrlForVariant(variantName))

.then(function (resp) {

if (resp.status >= 300) {

updateViewExplainingMissingVariant(variantName)

throw new Error("Could not load requested variant.")

}

return resp.json()

})

.then(addAssetsToDom)

})()

</script>

</body>

</html>You’ll note that we decided to inform the user of the missing variant in case it is unavailable, instead of just reloading on their behalf. Depending on the kinds of differences between variants, just loading the default variant might be too subtle for the user to realize something didn’t work. So, we display a very simple message.

The structure above expects the server to house all the variant information in

the /variants/ directory. That directory might look like this:

variants

├── mock.json

├── my_new_feature.json

└── public.jsonBut how do we build those files? This is where we need to customize our Webpack configuration.

webpack.config.ts

The code below will not work in your project unless you add loader rules to your Webpack config. Additionally, you may not have things set up to use TypeScript in your Webpack config, but the TypeScript in this code example is limited and easily removed.

import path from "path"

import { DefinePlugin } from "webpack"

import MiniCssExtractPlugin from "mini-css-extract-plugin"

import HtmlWebpackPlugin from "html-webpack-plugin"

type WebpackEnv = {

/** Webpack adds this boolean when running the dev server */

WEBPACK_SERVE?: boolean

/** This is the webpack env var that we're requiring from the CLI */

variantName: string

}

const defaultVariantName = "public"

const dir = path.resolve(__dirname)

/**

* This function can be replaced with anything that loads a particular

* config based on a variant name. In our codebase, we load some fairly

* intricate configuration files written in JavaScript. For simplicity

* though, I've hard-coded some values directly.

*

* The comments inside each variant help explain the imaginary state I

* am setting up, which is somewhat similar to what we use at Trilliant

* Health. As I said, though, this part is completely up to you. You can

* expose anything you want to your app via some kind of variant

* configuration, coupled with--in the case of Webpack--the

* `WebpackDefinePlugin`.

*/

function getVariantConfig(variantName: string) {

const variants = [

{

// This is what I'd consider the "production" version of the app.

// I call it public here because I don't want to confuse it with

// the Node environment name.

name: "public",

buildConfig: {

apiBaseUrl: "https://api.example.com",

auth0Audience: "http://stable-example.com/api",

auth0ClientId: "A92H...",

auth0Domain: "your-account.us.auth0.com",

mockServer: false,

},

},

{

// In this imaginary scenario, the mock server handles everything,

// so we don't need to provide a real server URL

name: "mock",

buildConfig: {

apiBaseUrl: "https://api-does-not-exist.example.com",

auth0Audience: "http://stable-example.com/api",

auth0ClientId: "A92H...",

auth0Domain: "your-account.us.auth0.com",

mockServer: true,

},

},

{

// Let's say that local development for the new feature is faster

// with a mock server. So for this variant, we are working on some

// new feature, but using our mock server to do so.

name: "my_new_feature_local",

buildConfig: {

apiBaseUrl: "https://api-feature-branch.example.com",

auth0Audience: "http://experimental-example.com/api",

auth0ClientId: "B93I...",

auth0Domain: "your-feature-account.us.auth0.com",

mockServer: true,

},

},

{

// This variant is fully integrated end-to-end, so we

// don't use the mock server. We can push this version up to the

// server to let our teammates see how work is progressing and how

// the actual new server endpoints are working.

name: "my_new_feature",

buildConfig: {

apiBaseUrl: "https://api-feature-branch.example.com",

auth0Audience: "http://experimental-example.com/api",

auth0ClientId: "B93I...",

auth0Domain: "your-feature-account.us.auth0.com",

mockServer: false,

},

},

]

const variant = variants.find((x) => x.name === variantName)

if (!variant) throw new Error("No variant found called " + variantName)

return variant

}

/**

* The Webpack config. Don't forget to specify a variant when you call

* it from the CLI:

*

* webpack --env variantName=public

*

*/

export default async (webpackEnv: WebpackEnv) => {

if (!webpackEnv.variantName)

throw new Error("You must specify a `variantName`.")

const variant = getVariantConfig(webpackEnv.variantName)

const entry = [`${dir}/src/index.ts`]

return {

// An example of how a variant's config can be used to add a mock

// server.

entry: variant.buildConfig.mockServer

? [`${dir}/src/mockServer.ts`, ...entry]

: entry,

output: {

// Fingerprint the image files

assetModuleFilename: "assets/images/[contenthash][ext]",

// Fingerprint the JS files

filename: "assets/js/[name].[contenthash].js",

path: "build",

publicPath: "/",

},

//

//

// NOTE: I have left out all the usual loader and file type

// configuration. It's up to you to merge the examples here with

// your actual Webpack configuration.

//

//

plugins: [

new MiniCssExtractPlugin({

// We want to fingerprint the CSS files, just like the JS files

filename: "assets/css/[name].[contenthash].css",

}),

// Examples of using the variant config to change constants inside

// the app

new DefinePlugin({

AUTH_0_AUDIENCE: JSON.stringify(variant.buildConfig.auth0Audience),

AUTH_0_CLIENT_ID: JSON.stringify(variant.buildConfig.auth0ClientId),

AUTH_0_DOMAIN: JSON.stringify(variant.buildConfig.auth0Domain),

API_BASE_URL: JSON.stringify(variant.buildConfig.apiBaseUrl),

}),

// Creates the variant dependencies JSON file:

// variants/{variantName}.json.

//

// The HtmlWebpackPlugin is really not meant for creating JSON

// files, but it is situated perfectly in the build process for

// this exact task. If you think about it, we are just replacing

// the use of `HtmlWebpackPlugin` as a way to inject our

// dependencies into "index.html" with the exact same files

// enumerated in a JSON file.

new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

inject: false,

minify: false,

templateParameters: (_compilation, assets, _tags, _opts) => ({

assets,

}),

templateContent: `{

"css": <%= JSON.stringify(assets.css) %>,

"scripts": <%= JSON.stringify(assets.js) %>,

}`,

// When running locally for development, we just use the default

// variant name as the name of the JSON file. The specified

// variant's settings will still be loaded, but you won't have

// to include a variant in your query params just for local

// development. (Remember, no variant is the same as loading the

// default variant. See the JavaScript in the index.html file)

filename: `variants/${

webpackEnv.WEBPACK_SERVE ? defaultVariantName : variant.name

}.json`,

}),

],

}

}This configuration will build our app into the build folder or serve it up via

the dev server when running locally. Assuming you fill in the missing loaders

and such to fit your needs, the config above will allow you to start a dev

server or build via the following command.

# compile and start the dev server for the my_new_feature variant

webpack serve --env variantName=my_new_feature

# build the public variant

webpack --env variantName=publicWhen you build, you’ll get something approximating the following folder output.

build

├── assets

│ ├── css

│ │ ├── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css

│ │ └── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css.map

│ ├── images

│ │ └── 71124d3ac27ba0a97f64.png

│ └── js

│ ├── main.dac8c08c71723ee316dc.js

│ └── main.dac8c08c71723ee316dc.js.map

├── index.html

└── variants

└── public.jsonIf you make a change and build again, you’ll get the exact same index.html,

but a different version of public.json and different asset files. The magic

happens when you push these files to your server and build a different

variant.

If we were to build the “mock” variant, the resulting build is similar.

webpack --env variantName=mockbuild

├── assets

│ ├── css

│ │ ├── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css

│ │ └── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css.map

│ ├── images

│ │ └── 71124d3ac27ba0a97f64.png

│ └── js

│ ├── main.486ca92fcb722bcd7339.js

│ └── main.486ca92fcb722bcd7339.js.map

├── index.html

└── variants

└── mock.jsonYou’ll see that the CSS and images are the same, but the JavaScript files are

different and we have a different variant JSON file named mock.json. If you

upload these files to your server alongside your previous uploaded files, you’ll

get something like the following.

(server)

├── assets

│ ├── css

│ │ ├── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css

│ │ └── main.2a70d927cdc35881336a.css.map

│ ├── images

│ │ └── 71124d3ac27ba0a97f64.png

│ └── js

│ ├── main.486ca92fcb722bcd7339.js

│ ├── main.486ca92fcb722bcd7339.js.map

│ ├── main.dac8c08c71723ee316dc.js

│ └── main.dac8c08c71723ee316dc.js.map

├── index.html

└── variants

├── mock.json

└── public.jsonNow, visiting your site at example.com will serve up the public variant

using main.dac8c[...].js while visiting example.com/?variant=mock will serve

up the mock variant using main.486ca[...].js.

Diverging even farther

I mentioned a few times above that the code here is similar to what we use at Trilliant Health. There are tons of little features we’ve layered on top of our variant system. We’ve layered in a CLI that builds and deploys multiple variants at once, so that you can have several variants all based on the latest changes in your main branch. We’ve added a way to cut and freeze versions of our application to allow internal users to work with older versions of a tool that depends highly on a rapidly changing data structure. We’ve deployed variants that allowed our marketing department personnel to capture images of our Similarity Index™ tools unencumbered by explanatory text. We’ve added descriptions to the internal variants and UI elements in the actual app that can read and understand which variants are available to give users a way to switch as needed.

|

|---|

| Had I just finished watching Marvel’s Loki series when I created this system? Maybe. Does our internal UI lean into that origin? Maybe. Icon available at Slackmojis.com. |

The possibilities are vast and the latitude you can gain from using a system like this is very freeing. (You know what else is freeing? Not doing automatic deployments when your PRs get merged to main. 😱 But that is a heretical rant for another time.)

App Variants in a Nutshell

Everything in the code above is just a single implementation of the idea of “app

variants”. And “app variants” is just a name I slapped onto a simple idea: By

moving the dependencies needed to boot your app into a file external to the

index.html, you can have multiple dependency definitions for multiple apps,

and you can write a bit of JavaScript to decide which app to load altogether.

Have you ever seen anyone else use this technique before? I’d love to know.

In any case, if these ideas are useful to you, please run with them! Let me know what works for you and what you needed to change.